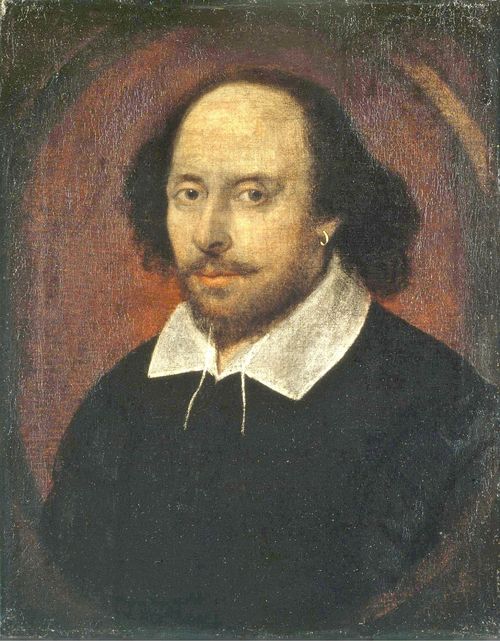

In the annals of history, few figures evoke as much intrigue and tragedy as Lady Jane Grey, the "Nine Days Queen" whose brief reign and untimely execution have captivated historians and storytellers for centuries. Executed at the age of just 17, Lady Jane Grey has long been remembered through posthumous portrayals that depict her as a helpless, blindfolded martyr. However, recent research has brought to light a potential breakthrough: a Tudor-era portrait believed to be the only known image of Lady Jane painted during her lifetime. This discovery, if confirmed, would offer an unprecedented glimpse into the life and appearance of one of history's most enigmatic figures.

The portrait in question has a storied history of its own. Long believed to be Lady Jane Grey, the attribution was rejected after more than 300 years, leaving its true identity shrouded in mystery. Now, experts from English Heritage, in collaboration with the Courtauld Institute of Art and dendrochronologist Ian Tyers, have uncovered compelling evidence suggesting that this painting may indeed capture the likeness of the teenage queen. The portrait is currently on loan to Wrest Park in Silsoe, Bedfordshire, where it has become the focus of intense scrutiny and fascination.

"Regardless of her identity, the results of our research have been fascinating," said Rachel Turnbull, senior collections conservator at English Heritage. Turnbull and her team employed a range of cutting-edge scientific techniques to uncover the painting's secrets. Infra-red reflectography revealed significant alterations made to the sitter's costume after the portrait was completed, including changes to her sleeves and coif—the linen cap worn over her hair. These modifications suggest that the original portrait may have depicted a more elaborate and regal attire, which was later toned down to reflect Lady Jane's posthumous image as a "subdued, Protestant" martyr.

One of the most striking discoveries was the deliberate defacement of the portrait. The sitter's eyes, mouth, and ears were scratched out, likely as part of an iconoclastic attack motivated by religious or political reasons. This act of vandalism mirrors similar marks found on a National Portrait Gallery image of Lady Jane, suggesting a pattern of deliberate desecration. According to Turnbull, these findings support the theory that the painting was altered to align with the prevailing narrative of Lady Jane as a Protestant martyr.

Dendrochronological analysis, which involves dating the painting's wooden panel through tree-ring patterns, revealed that the Baltic oak boards used for the portrait were likely sourced between 1539 and 1571. This timeline places the painting within Lady Jane's lifetime, lending further credence to its attribution. Additionally, the back of the panel bears a merchant or cargo mark identical to one found on a royal portrait of Edward VI, Lady Jane's predecessor. This connection suggests that the painting may have been commissioned during the tumultuous period of religious upheaval and political intrigue that defined the Tudor era.

Lady Jane Grey's story is one of extraordinary brevity and profound tragedy. Born in Bradgate Park, Leicestershire, around 1537, she was the great-niece of Henry VIII and received an education on par with the king's own daughters. Fluent in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, French, and Italian, Lady Jane was a highly educated and intelligent young woman. Her high-status family positioned her as a pawn in the larger game of Tudor politics, particularly as Protestant King Edward VI sought to prevent his Catholic sister Mary from ascending the throne.

When Edward VI died in 1553, Lady Jane was proclaimed queen by her father-in-law, the Duke of Northumberland. However, her reign lasted a mere nine days, from July 10 to July 19, before she was deposed in favor of Mary I. In the wake of a Protestant uprising against Mary, Lady Jane was executed at the Tower of London in 1554. Her refusal to convert to Catholicism cemented her legacy as a Protestant martyr, and she has since been depicted in countless posthumous portraits as a helpless, blindfolded figure facing the executioner's block.

The most famous portrayal of Lady Jane, "The Execution of Lady Jane Grey" by Paul Delaroche, painted in 1822, captures her as a vulnerable and tragic figure. This image, along with others, has long defined the public's perception of Lady Jane as a victim rather than a strong-willed and intelligent young woman. The newly examined portrait, however, challenges this traditional representation. Historical novelist and historian Philippa Gregory, who viewed the painting at English Heritage's conservation studio, noted that the features are strikingly similar to those in the National Portrait Gallery's depiction of Lady Jane. "This is such an interesting picture posing so many questions," Gregory said. "If this is Jane Grey, it is a valuable addition to the portraiture of this young heroine, as a woman of character—a powerful challenge to the traditional representation of her as a blindfolded victim."

The implications of this discovery extend beyond the realm of art history. If confirmed, the portrait would provide a rare and authentic glimpse into the life of Lady Jane Grey, offering a more nuanced understanding of her identity and the historical context in which she lived. It would also highlight the complex interplay between art, politics, and religion during the Tudor era, a period marked by intense conflict and upheaval.

Moreover, the portrait's history reflects the broader narrative of Lady Jane's life. Acquired by one of Wrest Park's former owners in 1701 as an image of Lady Jane Grey, it remained the defining portrait of the "Nine Days Queen" for over three centuries. However, as historical scrutiny increased, its attribution was eventually rejected, leaving its true identity in doubt. Peter Moore, the curator of Wrest Park, described the painting's return to the estate as "thrilling," noting that the new research provides "tantalising evidence" supporting its connection to Lady Jane.

The ongoing debate surrounding the portrait's authenticity underscores the enduring fascination with Lady Jane Grey. Her brief reign and tragic end have made her a symbol of both resilience and vulnerability, a young woman caught in the crossfire of religious and political tensions. The possibility that this painting captures her true likeness adds a new dimension to her story, inviting us to reconsider the traditional narrative and appreciate her as a complex and multifaceted individual.

In conclusion, the recent research into the Tudor-era portrait believed to depict Lady Jane Grey offers a tantalising glimpse into the life of one of history's most enigmatic figures. While definitive confirmation remains elusive, the evidence uncovered by experts from English Heritage and their collaborators presents a compelling case. The portrait's alterations, dendrochronological dating, and connection to other royal portraits all support the theory that this painting captures the true likeness of the "Nine Days Queen."

As historians and art enthusiasts continue to unravel the mysteries surrounding Lady Jane Grey, this portrait serves as a reminder of the importance of questioning established narratives and seeking new perspectives. Whether or not it is ultimately confirmed as Lady Jane, the painting invites us to reflect on the complexities of her life, the turbulent era in which she lived, and the enduring power of art to shape our understanding of the past.

By Eric Ward/Mar 27, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/Mar 27, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Mar 27, 2025

By Megan Clark/Mar 27, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/Mar 27, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Mar 27, 2025

By David Anderson/Mar 27, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Mar 27, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Mar 27, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Mar 27, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Mar 14, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Mar 14, 2025

By William Miller/Mar 14, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Mar 14, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Mar 14, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Mar 14, 2025