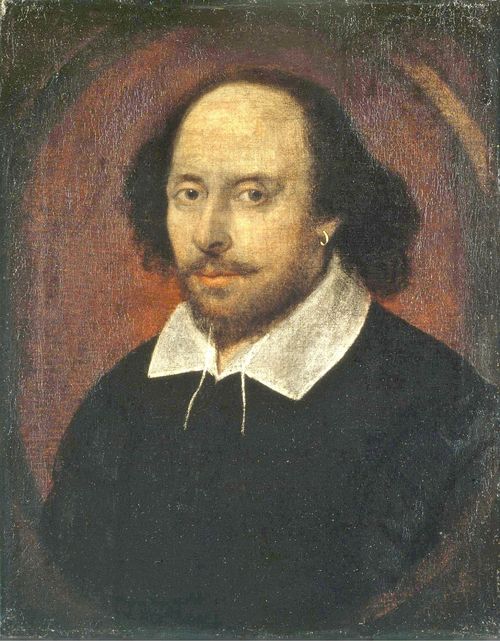

In a world increasingly dominated by digital deceptions and AI-generated falsehoods, it's easy to assume that the art of forgery is a modern phenomenon. Yet, the recent discovery of an elaborate art forger's workshop in Rome, along with the contentious debate surrounding a supposed masterpiece in London's National Gallery, serves as a stark reminder that the history of fraudulent art is as ancient as it is intricate. From impossible pigments to clumsy brushstrokes and suspicious signatures, the tale of art forgery is written in the very materials and techniques that artists have used for centuries.

On February 19th, Italy's Carabinieri Command for the Protection of Cultural Heritage uncovered a covert forgery operation in a northern district of Rome. Authorities seized over 70 fraudulent artworks, falsely attributed to renowned artists ranging from Pissarro to Picasso, Rembrandt to Dora Maar. Along with the counterfeit pieces, they confiscated materials used to mimic vintage canvases, artist signatures, and the stamps of defunct galleries. The suspect, still at large, allegedly used online platforms like Catawiki and eBay to sell these forgeries, complete with convincing certificates of authenticity. This case, while decidedly low-tech, highlights the enduring allure of deception in the art world.

The discovery in Rome was quickly followed by a sensational claim regarding a painting in London's National Gallery. According to artist and historian Euphrosyne Doxiadis, the gallery's prized "Samson and Delilah," attributed to 17th-century Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens, is not what it seems. Purchased in 1980 for £2.5 million, the painting is now alleged to be a crude imitation, centuries younger than its claimed date of 1609-10. Doxiadis's assertions are supported by a 2021 analysis by Swiss company Art Recognition, which used AI to determine a 91% probability that the painting is not by Rubens. The National Gallery, however, stands firm in its attribution, citing the work's "highest aesthetic quality" and a 1983 technical examination.

This divergence of opinion opens a fascinating space for reflection on the nature of artistic value and authenticity. As debates intensify around the integrity of cultural icons, both long-disputed and recently questioned, it becomes essential to arm oneself with the tools to navigate the murky waters of art forgery. Here are five simple rules to help spot a fake masterpiece:

Rule 1: Pigments Never Lie

To be a successful art forger requires not only technical skill but also a deep understanding of history and chemistry. Anachronistic pigments are often the giveaway. Consider the case of German forger Wolfgang Beltracchi, who specialized in creating "new" works by modernist masters like Max Ernst and André Derain. Beltracchi was meticulous about using historically accurate pigments, but a single mistake in 2006 sealed his fate. While fabricating a painting attributed to Heinrich Campendonk, he inadvertently used a tube of paint containing titanium white—a pigment unavailable during Campendonk's time. This minor oversight exposed the forgery, which had sold for €2.8 million.

Similarly, a portrait once attributed to Parmigianino and sold by Sotheby's for $842,500 was later revealed to contain phthalocyanine green, a synthetic pigment invented in 1935—centuries after the Renaissance artist's time. Artists may be visionaries, but they are not time travelers.

Rule 2: Keep the Past Present

Art without a verifiable history is inherently suspicious. Authentic artworks carry with them a rich tapestry of provenance—ownership records, exhibition histories, and documented sales. The absence of such a history should raise alarm bells, as it did with the forgeries of Dutch artist Han van Meegeren. Van Meegeren, one of the 20th century's most prolific forgers, created a series of fake Vermeers, including "Christ and the Men at Emmaus." Eager to believe these were lost masterpieces, collectors overlooked the glaring lack of provenance.

Van Meegeren's deception unraveled after World War II when he was charged with selling a Vermeer to Nazi official Hermann Göring. To prove the painting was a forgery, he demonstrated his ability to create a convincing Vermeer in front of experts. His admission exposed the extent of his fraud, highlighting the importance of a painting's history.

Rule 3: Squint

An artist's brushwork is as unique as their fingerprint. The pressure, texture, and flow of their strokes are nearly impossible to replicate, especially under the scrutiny of modern technology. British forger Eric Hebborn, who specialized in counterfeiting works by old masters, managed to overcome this challenge through an unusual method: alcohol. Hebborn used brandy to calm his nerves, allowing him to channel the gestures of the artists he impersonated. His forgeries from the 1970s and 1980s remain some of the most convincing, with institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art still attributing certain works to their original creators, despite Hebborn's involvement.

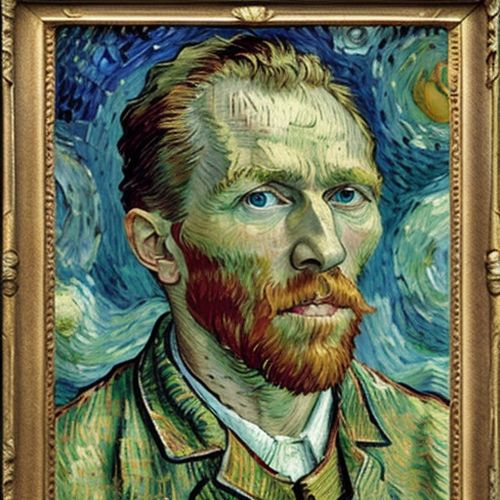

Rule 4: Go Deeper

When surface-level analysis proves inconclusive, deeper investigation may be necessary. Consider the case of a still life attributed to Vincent van Gogh. For years, experts debated its authenticity, citing inconsistencies in color and the lack of provenance. An X-ray in 2012, however, revealed that Van Gogh had reused the canvas, painting over an earlier work he referenced in a letter to his brother Theo. This discovery not only confirmed the painting's authenticity but also created a unique composite image, showcasing the artist's restless mind.

Rule 5: It's the Little Things That Give You Away

Sometimes, the smallest details can expose a forgery. In 2007, collector Pierre Lagrange paid $17 million for a painting falsely attributed to Jackson Pollock. The giveaway was a simple spelling error in the signature—Pollock's distinctive "c" before the final "k" was missing. This mistake not only exposed the forgery but also implicated the Knoedler & Co gallery, one of New York's oldest and most esteemed institutions. The gallery had sold numerous forgeries attributed to Rothko, De Kooning, and Motherwell, all supplied by a dubious dealer claiming the works came from an enigmatic "Mr. X." The scandal led to the gallery's closure after 165 years and the disappearance of the forger, Pei-Shen Qian.

The Future of Art Forgery

As technology advances, so too do the tools available to both forgers and those seeking to expose them. AI and machine learning offer new ways to analyze brushstrokes, pigments, and provenance, making it increasingly difficult for forgeries to slip through the cracks. Yet, the allure of deception remains. The recent discoveries in Rome and London remind us that the art world's fascination with authenticity is as enduring as the human desire to create.

In a time when digital deceptions are rampant, the lessons of art forgery offer a valuable reminder: truth lies in the details. From the pigments used to the history of a painting, from the unique gestures of an artist to the smallest spelling errors, authenticity is a complex tapestry woven from countless threads. As collectors, historians, and enthusiasts navigate the ever-evolving landscape of art, these simple rules serve as a guide, helping to distinguish the genuine from the counterfeit.

In the end, the art of forgery is not just a tale of deception but a testament to the enduring power of art itself. Whether a masterpiece or a convincing imitation, these works capture our imagination, challenge our perceptions, and remind us that the line between truth and falsehood is often finer than we might think.

By Eric Ward/Mar 27, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/Mar 27, 2025

By Emma Thompson/Mar 27, 2025

By Megan Clark/Mar 27, 2025

By Elizabeth Taylor/Mar 27, 2025

By Sarah Davis/Mar 27, 2025

By David Anderson/Mar 27, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Mar 27, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Mar 27, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Mar 27, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Mar 14, 2025

By Christopher Harris/Mar 14, 2025

By William Miller/Mar 14, 2025

By Emily Johnson/Mar 14, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Mar 14, 2025

By Victoria Gonzalez/Mar 14, 2025